Nutrition and Cancer Risk: Part 2

A Science-Backed Approach to Risk Reduction (Foods to Avoid)

In Nutrition and Cancer Risk Part 1, we explored how small, meaningful dietary choices can help reduce cancer risk over time. The goal isn’t perfection—it’s progress. Adding more plant-based foods, increasing fiber, and prioritizing whole, nutrient-dense meals all contribute to cumulative protection against cancer.

But what about the other side of the equation? Are there foods that actively increase cancer risk? What does the evidence really say?

In this post, we’ll dive into some of the most common questions I get in my practice:

Red and processed meat: How much is too much, and what are the best ways to reduce risk?

Organic vs. conventional foods: Are pesticides really a major cancer concern?

Soy and estrogen-driven cancers: What’s fact, and what’s fear-mongering?

Artificial sweeteners: Do they really cause cancer, or is this just another nutrition myth?

We live in an age where social media can sometimes make it feel like we're constantly at risk from toxins in our food—from pesticide residues on produce to artificial additives like food dyes. While these concerns are not entirely unfounded, the data shows that the real culprit in increasing cancer risk is often not what’s in our food, but rather what’s missing. This isn’t about fear-based diet choices. It’s about understanding the science so you can make informed, practical choices that support long-term health.

“The real culprit in increasing cancer risk is often not what’s in our food, but rather what’s missing.”

Studies consistently demonstrate that cancer risk is more closely linked with a diet lacking nutrient-dense, whole foods rather than the contaminants found in conventionally grown produce or the occasional red meat meal. Most of the risk associated with diet comes from not getting enough of the “good stuff”—fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and other plant-based foods that are rich in antioxidants, fiber, and other bioactive compounds that protect our cells.

Remember, the focus is on adding positive, nutrient-rich foods to your plate rather than obsessing over every potential toxin. By concentrating on what we can control—like incorporating more whole foods and making gradual changes—we empower ourselves to take charge of our health without getting overwhelmed by misinformation.

Let’s get into the details and practical strategies that can help you make informed, balanced choices without fear.

Red Meat and Processed Meat — Understanding the Risks

The relationship between red and processed meat consumption and cancer risk has been a topic of extensive research. While these foods are staples in many diets, large-scale studies suggest that consuming high amounts of red and processed meats increases the risk of certain cancers, particularly colorectal cancer.1

Recent data has further strengthened this association, with possible links to other gastrointestinal cancers as well. The increased risk appears to stem from several biological processes, including the formation of carcinogenic compounds, changes in gut bacteria, and chronic inflammation.

How Do Red and Processed Meats Increase Cancer Risk?

How meat is cooked and processed significantly impacts its cancer risk.

High-temperature cooking methods like grilling and frying create heterocyclic amines (HCAs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)—compounds that can damage DNA and promote cancer.

Processed meats—including bacon, sausages, hot dogs, deli meats, and beef jerky—contain N-nitroso compounds (NOCs), which are known to be carcinogenic. These compounds form during the curing and preservation process, increasing cancer risk.

Red meat naturally contains heme iron, which can promote the production of free radicals and oxidative stress in the gut, potentially leading to DNA damage.

Impact on Gut Health and Inflammation

A diet high in red and processed meats may promote pro-inflammatory gut bacteria, increasing the risk of colorectal cancer.

Eating large amounts of red meat stimulates bile acid production, which can lead to secondary bile acids—compounds that have been linked to an increased risk of gastrointestinal cancers.

Processed vs. Red Meat: What’s the Difference?

While both red and processed meats have been linked to cancer risk, the concern is stronger for processed meats.

Processed meat refers to meat that has been preserved through smoking, curing, salting, or chemical additives. These processes introduce carcinogenic compounds, making them more strongly linked to colorectal cancer than fresh red meat.

Red meat, including beef, pork, lamb, and veal, has been classified as “probably carcinogenic”, but the risk is primarily associated with high-temperature cooking methods rather than preservation techniques.

What Does the Research Show?

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), a division of the World Health Organization (WHO), has determined:

Processed meat is classified as a 'Group 1 carcinogen' by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), meaning there is sufficient evidence that it increases cancer risk, particularly for colorectal cancer.

Red meat is classified as a ‘Group 2A carcinogen’ meaning there is limited evidence linking it to cancer, but the association is not as strong as with processed meat.

Putting the Risk in Perspective

The link between red and processed meat and cancer may sound alarming, but it’s important to put the absolute risk into perspective

Consuming processed meat daily over long periods may increase lifetime colorectal cancer risk by approximately 1–2%. For example, if a person’s baseline risk is 5%, frequent processed meat consumption could raise it to 7%

Now compare this to smoking, which is also classified as a Group 1 carcinogen:

A lifelong non-smoker has about a 1-2% chance of developing lung cancer.

A pack-a-day smoker has about a 15-20% lifetime risk.

This means smoking increases risk by 14-18%, a far greater effect than processed meat consumption.

So while processed and red meat consumption is a risk factor, it is nowhere near the magnitude of risk posed by smoking. Moderation, along with a diet rich in whole, plant-based foods, may also help mitigate this risk without requiring complete elimination of meat.

If you enjoy red and processed meats, the good news is that you don’t have to cut them out completely—small changes can significantly reduce risk.

Choose Healthier Cooking Methods

Opt for baking, steaming, or slow-cooking instead of grilling or frying to minimize HCAs and PAHs.

Use marinades with citrus, garlic, or rosemary, which may help reduce carcinogenic compound formation.

Avoid charring meat and trim off blackened portions.

Limit Processed and Red Meat Consumption

Limit red meat to 12-18 ounces per week and choose fresh, unprocessed cuts.

Reduce processed meat intake—treat bacon, sausages, and deli meats as occasional indulgences rather than dietary staples.

Incorporate alternative protein sources such as fish, poultry, beans, tofu, and lentils.

Eat More Protective Foods

A high-fiber diet (vegetables, fruits, whole grains) helps counteract harmful compounds in meat.

Cruciferous vegetables (broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts) contain compounds that may help detoxify carcinogens.

Antioxidant-rich foods like berries, nuts, and leafy greens help neutralize oxidative stress.

Adopt a Healthy Lifestyle

Regular exercise improves gut health and reduces inflammation.

Maintaining a healthy weight is critical, as obesity is a major cancer risk factor.

Cut back on alcohol and quit smoking—both of which have much stronger carcinogenic effects than meat.

Final Thoughts: A Balanced Approach

The research is clear—processed meat definitively increases cancer risk, and red meat probably does. However, the absolute risk increase is modest, especially compared to higher-risk factors like smoking.

Instead of focusing on eliminating red meat entirely, a more realistic approach might be to moderate consumption, use healthier cooking methods, and balance your diet with fiber-rich, plant-based foods.

Remember, it’s just one piece of the bigger puzzle. Think of your diet as a series of small, cumulative choices that add up over time. Cutting back on red and processed meats, increasing fiber from whole plant foods, and incorporating more antioxidant-rich fruits and vegetables all work together to support long-term health.

By making small, thoughtful changes, you can significantly reduce cancer risk while still enjoying the foods you love in a practical and sustainable way.

Organic Versus Non-Organic: What Really Matters for Cancer Prevention?

Many of my patients ask whether organic foods are healthier than conventional ones, often worrying about pesticides and long-term risks. While these concerns are understandable, the most important thing for cancer prevention is simply eating plenty of fruits and vegetables. Fruits and vegetables are packed with nutrients, fiber, and antioxidants that support health. If fear of pesticides discourages you from eating enough produce, the harm may outweigh the risk.

It’s important to recognize that food safety standards in the United States are rigorous. The FDA’s Pesticide Residue Monitoring Program consistently reports that most fruits and vegetables contain pesticide residues well within established safety limits. In this context, the risk from pesticide residue exposure in conventionally grown produce is generally low. However, it is not zero, and for patients who are especially concerned about cumulative exposure or are more vulnerable, selecting organic options can be a reasonable recommendation.

Low, but Not Zero, Exposure:

Data from the FDA’s Pesticide Residue Monitoring Program consistently indicate that the vast majority of fruits and vegetables have pesticide residues well within safety limits.

Nonetheless, studies have shown that organic produce tends to have lower or undetectable levels of these residues compared with conventionally grown alternatives. For example, a study published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry compared pesticide residues in conventional, integrated pest management (IPM), and organic foods, and found that organic produce consistently had lower residue levels.2

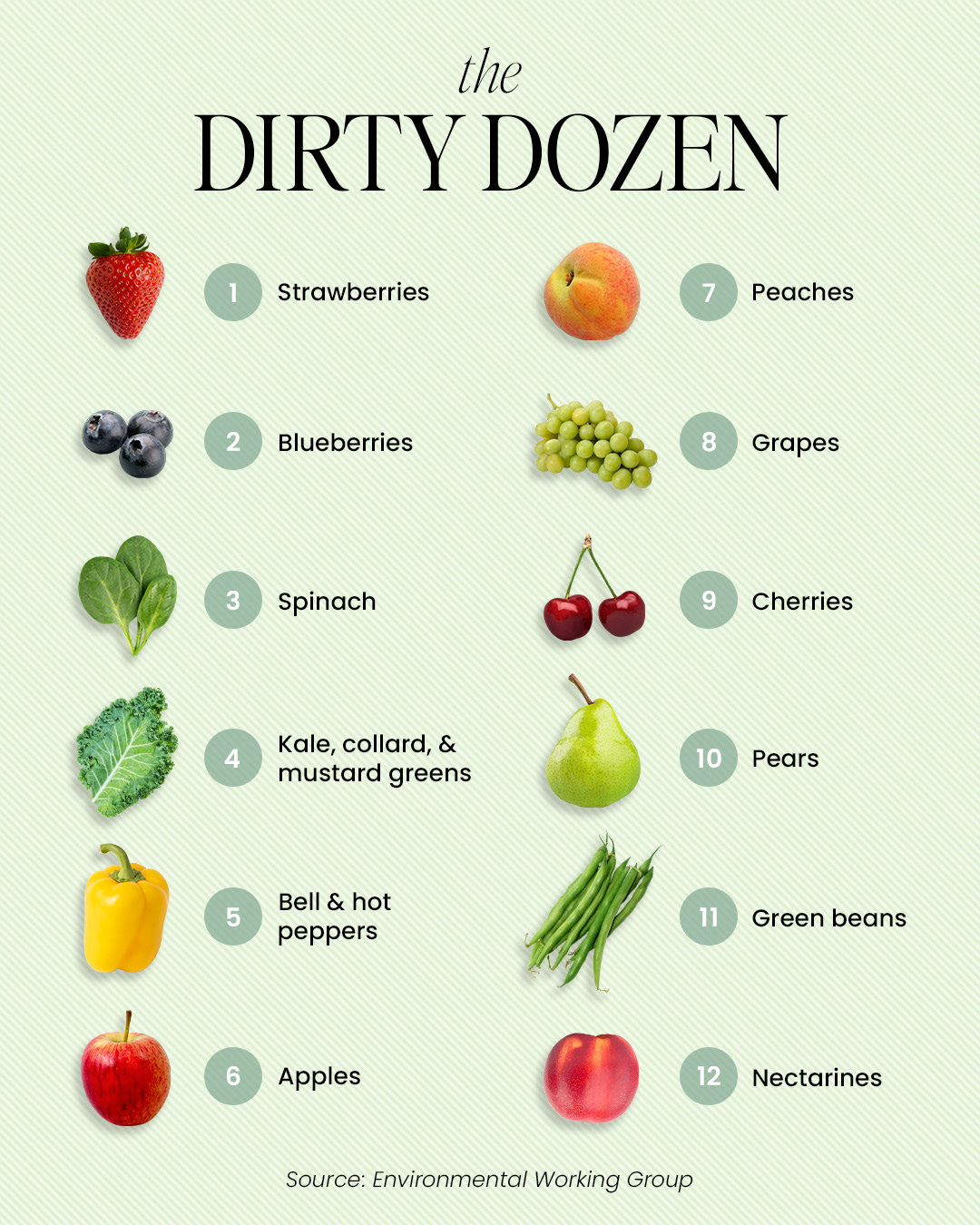

When prioritizing organic purchases, consider using the Environmental Working Group’s (EWG) lists:

'Clean Fifteen': Fruits and vegetables least likely to have pesticide residues.

'Dirty Dozen': Produce more likely to contain higher pesticide residues.

For patients on a budget, it’s useful to note that certain types of produce consistently show lower pesticide residue levels. The Environmental Working Group (EWG) annually publishes the “Clean Fifteen” list, which highlights fruits and vegetables that tend to have the lowest pesticide residues. If patients have concerns and would like to prioritize organic options for produce, I often refer to the “Dirty Dozen” list (items more likely to contain higher levels of pesticide residues) can be an effective, cost-conscious strategy.3

Practical Steps—Washing Produce:

Even for those choosing conventionally grown produce, thorough washing can reduce pesticide residues. One study on pesticide residues during the washing of fruits and vegetables found that simply rinsing produce under running water can reduce pesticide residues by roughly 30% to 80%, depending on the type of pesticide, the produce’s surface characteristics, and the washing method used. Rinsing under running water and using a brush for items with thicker skins can remove a significant proportion of surface residues. While washing doesn’t eliminate pesticides that have been absorbed into the tissue, it does reduce the overall exposure and can be a helpful practice.4

Broader Perspective on Cancer Prevention:

It’s important to reiterate that dietary choices, including the decision to purchase organic, are one component of a broader cancer prevention strategy. The benefits of a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins, along with maintaining a healthy weight and regular physical activity, far outweigh the relatively small risks posed by low-level pesticide residues.

Soy and Risks for Estrogen-Dependent Cancers:

One common question I receive—especially from women with a history of estrogen-dependent cancers like breast and endometrial cancer—is whether soy or soy milk is safe to consume. The concern arises from soy’s isoflavones, a type of phytoestrogen that can weakly mimic estrogen in the body. Since estrogen can fuel some types of cancers, it's natural to wonder if soy-based foods has a similar effect.

Breast Cancer Risk and Soy:

Large studies, especially in Asian populations where soy is a dietary staple, show no increased breast cancer risk from soy consumption. In fact, many suggest it may be protective.5 A meta-analysis published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention found that women with higher soy intake had a lower risk of developing breast cancer compared to those with low intake.

Early lab studies raised concerns as high doses of isoflavones stimulated estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cells in vitro. However, these levels far exceeded typical dietary intake. More recent clinical studies indicate that typical dietary soy intake does not stimulate breast tissue growth and may even provide benefits, due to favorable estrogen metabolism.

Soy and Endometrial Cancer

Research on soy and endometrial cancer has not demonstrated a harmful effect. Like with breast cancer, most evidence suggests moderate soy intake is safe as part of a balanced diet.

Why Soy is Safe:

Soy isoflavones bind to estrogen receptors, but much more weakly than natural estrogen. They preferentially bind to estrogen receptor beta (ERβ), which may actually counteract estrogen’s more proliferative effects. This receptor selectivity could explain why soy appears more protective than harmful.

Practical Takeaways

Moderation is Key – Consuming soy in moderation (e.g., tofu, tempeh, soy milk, edamame) as part of a diverse diet is unlikely to increase cancer risk and may offer benefits.

Choose Whole Soy Foods Over Supplements – Whole soy foods contain a natural balance of nutrients, while concentrated soy supplements may have different effects.

Personalized Approach – Women with a history of estrogen-dependent cancers can generally include moderate soy intake in their diet. However, discussing individual concerns with a healthcare provider is always a good idea.

In summary, moderate soy consumption is not only safe but may be beneficial, particularly when sourced from whole foods. If concerns persist, a personalized discussion with a healthcare provider can help guide dietary choices.

Artificial Sweeteners and Cancer: Sorting Fact from Fear

This is another common topic I discuss in the clinic. Artificial sweeteners have been debated for decades. Some claim they’re a helpful tool for reducing sugar intake, while others fear they increase cancer risk, disrupt metabolism, or lead to long-term health problems. With all the conflicting messages, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed.

So, what does the research actually say?

Do artificial sweeteners increase cancer risk?

Are some sweeteners riskier than others?

Should you avoid them entirely or just consume them in moderation?

This post isn’t about hype or fear—it’s about the science. Let’s break it down.

Where Did the Cancer Concerns Come From?

Concerns over artificial sweeteners and cancer originated in the 1970s when saccharin was linked to bladder cancer in rats. That led to warning labels and widespread public concern. But decades of follow-up research showed that:

The mechanism that caused cancer in rats does not apply to humans.

Large-scale human studies found no connection between saccharin and cancer.

By 2000, saccharin was officially removed from the list of potential carcinogens.

Since then, other artificial sweeteners—aspartame, sucralose, acesulfame potassium (Ace-K)—have faced similar scrutiny. Some studies have suggested a possible association between high artificial sweetener intake and certain cancers, like liver or kidney cancer, but many well-designed studies have found no meaningful connection.

A major challenge in studying artificial sweeteners is confounding factors. People who consume them often have different lifestyles, diets, or pre-existing health conditions than those who don’t. Many turn to diet sodas and sugar substitutes because they’re already managing weight, diabetes, or metabolic issues—all of which are independent cancer risk factors.

When researchers adjust for these factors, most studies find no strong evidence that artificial sweeteners increase cancer risk at normal intake levels.

Let’s take a closer look at the evidence, sweetener by sweetener.

Breaking Down the Research on Individual Sweeteners

Saccharin (Sweet’N Low, pink packet)

Saccharin was the original artificial sweetener to be linked to cancer, but the bladder cancer risk was only found in rats. After decades of research, we now know that this effect does not translate to humans.

Human studies have found no increased risk of cancer from saccharin.

Regulatory agencies worldwide consider it safe for consumption.

The National Toxicology Program removed saccharin from its carcinogen list in 2000.

The early cancer scare was unfounded. Saccharin is safe in moderation.

Aspartame (Equal, NutraSweet, Diet Coke, sugar-free gum)

Aspartame has been one of the most controversial sweeteners, with concerns about brain tumors, liver cancer, and metabolic effects. Some studies have raised concerns, particularly in individuals with pre-existing risk factors, but high-quality human research does not support these fears.

A 2022 review in Environmental Health Perspectives found no consistent evidence that aspartame increases cancer risk.

Aspartame breaks down into methanol, phenylalanine, and aspartic acid, all of which occur naturally in other foods, such as fruits and proteins.

The FDA, EFSA (European Food Safety Authority), and WHO all consider aspartame safe at normal intake levels.

Dr. Peter Attia provides an excellent analysis of the limitations in studies evaluating aspartame and cancer risk: https://peterattiamd.com/aspartame-and-cancer/. Dr Attia notes that many the studies in rats and mice involved aspartame doses exceeding the FDA’s acceptable daily intake (ADI) for humans of 50 mg/kg of body weight. This would corresponds to about twenty 12-oz cans of diet soda every day. Even when studies examined doses within the ADI limit, they did not accurately reflect typical human consumption..

No solid evidence links aspartame to cancer at normal consumption levels. If you’re concerned, I would consider choosing an alternative like sucralose.

Sucralose (Splenda, yellow packet)

Sucralose has been widely studied and is not known to cause cancer in humans. Some early concerns were raised about DNA damage in lab settings, but human studies do not support this.

A 2017 meta-analysis in Critical Reviews in Toxicology found no significant cancer risk from sucralose.

A 2023 study in the Journal of Toxicology suggested that sucralose-6-acetate (a byproduct of sucralose metabolism) may damage DNA in lab tests, but the doses used were much higher than real-world consumption.

No strong evidence links sucralose to cancer, but ongoing research is evaluating long-term effects.

Acesulfame Potassium (Ace-K, found in diet drinks and protein shakes)

Ace-K has been linked to a slight increase in cancer risk in some animal studies, but these findings have not been consistently replicated in humans.

A 2021 review in Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology found no strong link between Ace-K and cancer.

Ace-K is rapidly excreted by the body, meaning it does not accumulate in tissues.

More research is needed, but no strong evidence suggests a cancer risk at normal intake levels.

The Bigger Picture: Obesity and Cancer Risk

While artificial sweeteners may not be a major cancer risk, a much bigger concern is obesity. Excess body fat is a proven risk factor for at least 13 types of cancer, including:

Breast cancer

Colorectal cancer

Pancreatic cancer

Endometrial cancer

Some studies suggest artificial sweeteners may contribute to weight gain by increasing cravings for sweet foods, but the best-designed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) show that replacing sugar with artificial sweeteners can help with weight control.

A 2023 review in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition found that swapping sugar for artificial sweeteners led to modest weight loss in most people.

Since obesity is a much bigger cancer risk factor than artificial sweeteners, a more important question is: If artificial sweeteners help reduce sugar intake and maintain a healthy weight, could they actually lower your overall cancer risk?

Final Verdict: Should You Be Worried About Artificial Sweeteners?

The bulk of scientific evidence suggests that, when used in moderation as part of an overall healthy diet, artificial sweeteners are unlikely to significantly increase cancer risk. In my practice I generally recommend trying to drink more water diet instead of beverages with caffeine which can be dehydrating. Also I counsel to focus on overall dietary quality and weight management, and use artificial sweeteners as one tool among many to reduce sugar intake without undue concern. If you have specific worries or underlying conditions, discussing them with a healthcare provider can help tailor the best approach for your needs.

7 Actionable Steps for Reducing Cancer Risk Through Diet

Limit processed meats (bacon, sausage, deli meats) to occasional consumption and prioritize fresh, unprocessed meats.

Use healthier cooking methods like baking or steaming instead of grilling or frying at high temperatures.

Incorporate more plant-based foods, including fiber-rich vegetables, fruits, and whole grains.

Choose organic selectively—prioritize organic for "Dirty Dozen" foods but focus more on eating a variety of produce.

Consume soy in moderation from whole food sources like tofu, tempeh, and edamame.

Use artificial sweeteners in moderation, but don't fear them at normal consumption levels.

Prioritize overall lifestyle habits like regular exercise, maintaining a healthy weight, and limiting alcohol.

Yep, that was a lot of information—but I hope you found it helpful! My goal with this series is to break down the science into practical, actionable steps that make a real difference. Remember, it’s not about perfection—it’s about small, meaningful changes that add up over time.

In the next part of this series, we’ll dive into the science of exercise and its ability to lower cancer risk. We’ll explore how physical activity influences everything from inflammation to immune function, and I’ll share practical ways to incorporate movement into your daily routine—whether you’re just getting started or looking to optimize your training.

I hope you’ll join me for that discussion!

Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev (2024) 33 (3): 400–410.

Baker, B. P., Benbrook, C. M., Groth, E., & Benbrook, K. L. (2002). "Pesticide Residues in Conventional, Integrated Pest Management (IPM)-grown, and Organic Foods: Insights from Three US Data Sets." Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 50(21), 6117–6126.

Environmental Working Group. "Clean Fifteen." EWG Clean Fifteen List.

Keikotlhaile, B. M., & Spanoghe, P. (2011). "Factors affecting removal of pesticide residues during washing of fruits and vegetables." Journal of Food Science, 76(1), R6–R15.

Boutas I, Kontogeorgi A, Dimitrakakis C, Kalantaridou SN. Soy Isoflavones and Breast Cancer Risk: A Meta-analysis. In Vivo. 2022 Mar-Apr;36(2):556-562.

So informative to cancer patients, this truly summaries all the things we want to know in a very straightforward manner. Thank you!!

Very informative, thank you!